Mar 12

Vincent Randazzo Makes Mischief with a Smile in Huntington's 'The Triumph of Love'

Kilian Melloy READ TIME: 7 MIN.

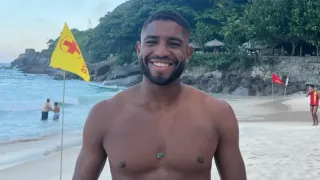

Brooklyn-based actor Vincent Randazzo is set to make his debut with The Huntington Theatre Company as Harlequin in Pierre Carlet de Chamblain de Marivaux's 1732 play "The Triumph of Love," which is currently running at the Huntington Theatre through April 6. (More information at this link.)

Written at the dawn of the Enlightenment, the play embraces the idea, only then coming back into vogue, that rational thought has a more direct bearing on objective reality than impulse, intuition, or feelings. But feelings are important, too, since they play a crucial role in human life – none more so, perhaps, than love.

Such, at least, is the play's message as it presents the story of Léonide, a princess whose uncle usurped the throne years before. She has fallen in love with the kingdom's rightful heir, Agis. The problem is that Agis has been raised by a famous philosopher, Hermocrates, who has rejected feelings – erratic and prone to error as they are – for the clarity of reason. Hermocrates has also raised Agis to believe that Léonide is his enemy, since Hemocrates assumes that Léonide would do anything to protect her status.

He's wrong about that; having fallen in love with Agis, Léonide wishes to restore him to the throne. The fact that she wants to marry him means that she will keep her position in society, but that's of secondary importance. In order to fulfill her heart's wishes, however, she's going to have to rely on her wit, cooking up an ingenious scheme to outmaneuver the philosophy of Hermocrates even as she conquers Agis' affections.

Cue that ever-reliable (and implicitly homoerotic) engine of comedic chaos: Cross-dressing as a means of disguise. In male garb – along with her maid, Corine, similarly disguised – Léonide infiltrates the household of Hermocrates and proceeds to make everyone there (including his sister, Léontine) fall in love with her. The plot threads quickly twist into a Gordian knot of compounded lies and desperate stratagems, with an all-around not-so-subtle frisson of same-sex desire. The play's suspense grows as the question looms: What Sword of Damocles will sever this particular gnarl? The truth? Or love itself? One outcome will spell disaster, while the other might somehow lead to a happy ending.

It's Harlequin, EDGE suggests to Randazzo, who helps keep the play's comedic sensibilities on track even as the heroes of the piece engineer one seduction after another. Otherwise, audiences could get a "Fatal Attraction" vibe and start wondering if any bunnies are going to get boiled. Harlequin's instant penetration of Léonide's disguise leavens the layers of deceit, allowing "The Triumph of Love" to assume a more benign affect.

"Absolutely!" the ACT-trained actor agrees. "It is bright, and there is levity. The play should be taken in that spirit. It hearkens to the change that the characters are going to go through by allowing this spirit of, 'We want the money,' and 'We want the fun'" on the part of Harlequin.

But he's not in it just for the gold coins Léonide slips him. "I think he's definitely a romantic," Randazzo adds of Harlequin. "I think he falls in love every day. When he does, he gives his heart completely and goes above and beyond for the object of his affection."

Randazzo gave EDGE the rundown on thoughts vs. feels – a point of contention even now, when people can't agree on simple facts – translator Stephen Wadsworth's supple English rendering, and what makes Harlequin the "beating heart" of the play.

EDGE: Do you see this as a play that pits reason against emotion – or as encouraging a reconciliation between reason and emotion?

Vincent Randazzo: I think it's the reconciliation. I think you need both. I think especially when you look at Léonide, she uses both to entice all three of these people and ingratiate them to her. I think what ultimately makes a human being is reason and emotion butting up against one another, or mixing together.

EDGE: The translation, by Stephen Wadsworth is very much contemporary, fluent English. It's not some sort of stilted, weird-sounding translation.

Vincent Randazzo: Yes, particularly when it comes to some of my wordplay. You would think it would come out like a Shakespeare sense of humor, but it's very much things that we understand now, in the 2020s. I thought that the balance of finding those places was so delicate, and also so deftly accomplished in the translation.

EDGE: It also gives your character, Harlequin, more of a worldly affect. He doesn't seem like a fool or clown – he's the sort of person you would expect to have a wild weekend.

Vincent Randazzo: Yes, he is. He encompasses a lot more. He's not a creepy clown where he's constantly horning on someone. He's not completely dim. He sometimes gets a little carried away because he feels so much of the world. This is such an opportunity to break the rhythms and shake things up that when it happens, he can't help himself; he would be completely taken over the moon about the ability to use his language, and he uses all that he has to offer.

EDGE: Harlequin is a borrowing from commedia dell'arte, but he fits into this play seamlessly. How are you dealing with the fact that he's coming from a different genre?

Vincent Randazzo: That's been a constant conversation between me and [director] Loretta [Greco]: How much commedia do we want? Because that changes what you do and what your intentions are as a character, if you're really committing to the commedia style, which is very much [rapid-fire patter] "da-da-da, da-da-da-da-da!" versus the flavor of commedia. Harlequin has a foundation of that, but he's so much more in their world; he's just a little bit different. I think Léontine and Hermocrate keep him around because he's the heart they may be lacking. He says, "I know more about the affairs of the heart than anybody else around here," and I think there's real truth in that.

EDGE: Do you think you have a little bit of Harlequin – or Trickster, or Loki, any general mischief maker – in you that you're drawing on for this?

Vincent Randazzo: For sure! [Laughing] I've played lots of different types of clowns, but this type of clown is probably the most different from me. He's in on it with the audience. He knows what's going on. He maybe judges the other servants. He's a bit sharper, a bit meaner, a touch more cynical, but the heart of Harlequin is definitely mine. The mischief with a smile is something I'm fully pulling from my own life. I love making people laugh. I like being silly, but I like to do it with a glint of, "I want to see if I can push your buttons just a touch." That comes from love, but every once in a while it's good to get a little spiky with people, just to see how they react.

EDGE: There's a queer vibe in any play where comedy arises from people pretending to be the opposite sex. That's definitely true here, and I think Harlequin is the one who's most in on that joke.

Vincent Randazzo: Oh, I would say so. From the very first time he sees them, and he says, "Speak up men! Are you women?" He hasn't even gotten confirmation that they are, but he doesn't really care. He sees their, whatever their gender is, is not a strictly, "Oh, because they're women, now I'm interested. I'm attracted to them." It's, "What a world is this, what magnificence is happening that I see these beautiful men that are also women! What a fantastic thing I'm experiencing! We needed something like this – we needed to shake up the dynamic."

When Hermocrate is telling Agis [about Léonide], he confesses, "This is who I'm going to marry."

He says, "She comported herself as the prettiest boy."

Léonide and Corine have something about them. It is sort of immaterial if they are men or women. They have beauty, they have love, they have heart. There is something attractive about them – physically and emotionally and intellectually – that is stimulating all of the characters. Léonide and Corine say who they are, but [what they say] also changes every other scene, and it doesn't change any of the other characters' affinity towards them.

EDGE: Do you think of Harlequin as something of a court jester?

Vincent Randazzo: I've toyed with that. I think he has responsibilities. I think he's had a solitary existence, up until this point, with Hermocrate and Léontine, and his musings and his talents have just not been put to use, so I think a lapsed court jester would be the way to describe him. He's been out of work for a minute, and now he's like, "Oh man, it's my time."

"The Triumph of Love" runs March 7 – April 6 at the Huntington Theatre Company. For tickets and more information, follow this link.