February 14, 2021

No Longer an Outlier: New York Ends Commercial Surrogacy Ban

David Crary READ TIME: 4 MIN.

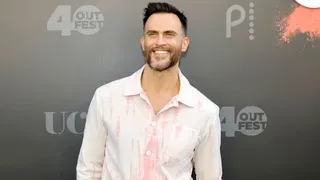

To become a father of two daughters, New York state Sen. Brad Hoylman and his husband made cross-country trips to California, where the girls were born through surrogacy arrangements.

At the time, New York was one of a handful of states outlawing commercial surrogacy. Now, it's about to become legal after years of activism by Hoylman and a host of allies who finally overcame tenacious political opposition.

Instead of being a national outlier, New York will become a leader, according to experts on surrogacy. They say the new law, passed in April and taking effect on Monday, has a surrogates' bill of rights providing the nation's strongest protections for women serving as surrogates.

Among the provisions: the right to independent legal representation, a guarantee of comprehensive medical coverage, and the right to make their own health care decisions, including whether to terminate or continue a pregnancy.

"We went to California because it had the best laws," Hoylman said. "Now New York has the best law. We think it's a model for other states."

The new law allows gestational surrogacy on a commercial basis, involving a surrogate who is not genetically related to the embryo. An egg is removed from the intended mother, fertilized with sperm and then transferred to a surrogate – in contrast to so-called traditional surrogacy that involves an egg from the surrogate. The gestational option is welcomed by many LGBTQ people who want to be parents, as well as by couples struggling with infertility.

With the change in New York, surrogacy advocates say only Louisiana and Michigan have laws explicitly prohibiting paid gestational surrogacy. Nebraska has no explicit ban, but a statute there says paid surrogacy contracts are unenforceable.

Hoylman, who was the surrogacy bill's lead sponsor in the New York Senate, and his husband, filmmaker David Sigal, made about 10 trips to California between them to help oversee the arrangements that led to the births of their daughters, Silvia, now 10, and Lucy, 3.

Gestational surrogacy routinely costs between $100,000 and $150,000. Hoylman declined to estimate the total costs incurred by him and Sigal but said, "It was worth every penny."

Among the standard costs are fees for lawyers and the surrogacy agency, the cost of in vitro fertilization, plus compensation and health insurance for the surrogate. Compensation rates vary widely – generally $25,000 to $50,000.

The first bill seeking to repeal the New York ban was introduced by Asemblywoman Amy Paulin in 2012, the year Hoylman was elected to the Senate. It floundered for years in the face of staunch opposition by the Roman Catholic Church and some feminists, who argued that paid surrogacy led to the exploitation of women.

"Under this bill, women in economic need become commercialized vessels for rent, and the fetuses they carry become the property of others," renowned feminist Gloria Steinem wrote to lawmakers in 2019.

New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo, who earlier in his tenure pushed hard to legalize same-sex marriage, argued in response that the surrogacy ban was "based in fear, not love" and was especially harmful to same-sex couples.

A leading surrogacy expert in California, Parham Zar, says gay couples and single men have constituted about half of his clientele in 20 years as managing director of the Egg Donor & Surrogacy Institute in Beverly Hills.

The institute has overseen more than 1,200 surrogacy births during that period, according to Zar, and he now plans to open an office in New York City. He expects that an expanded clientele will include many foreigners from countries where surrogacy is sharply restricted or illegal.

Zar says he advises clients to be braced for at least $100,000 in costs for a gestational surrogacy.

The bills can be higher. Andrew Kabatchnick, an accountant from White Plains, New York, says he and his wife, occupational therapist Leah Marx, have spent $250,000 to $300,000 on two gestational surrogacy births. Their 2-year-old daughter, Sophie, was brought to term by a surrogate in Alabama; a second baby is due in June via a surrogate in Arkansas.

Kabatchnick says it was "an easy decision" to have a second child, though he acknowledges the costs could be burdensome for many couples.

Kabatchnick and Marx have been clients of attorney Vicki Ferrara, founder and legal director of Worldwide Surrogacy in Fairfield, Connecticut.

She is impressed by New York's new law, saying it "brings surrogacy into a new realm of ethics that we haven't seen in other states."

For example, she said, ethical surrogacy practices that are optional in some states will now be statutorily required in New York. And no out-of-state surrogacy agency can operate in New York without obtaining a state license, thereby becoming obligated to follow the new regulations.

Ferrara hopes New York will push for careful screening of surrogates and intended parents before any contracts are signed.

"We're asking people who don't know each other to come together to bring a baby into the world," she said. "We need to have both the intended parents and the surrogate protected so the baby is brought into a situation that is really positive."