Apr 25

NYC Pride Unveils Grand Marshals for 2025 March

READ TIME: 4 MIN.

The following is a press release from EDGE OUTreach partner New York City Pride

NYC Pride | Heritage of Pride unveils its lineup of Grand Marshals for the 2025 NYC Pride March. Joining the ranks of honor this year are Karine Jean-Pierre, Marti Gould Cummings, DJ Lina, Elisa Crespo, and Trans formative Schools. NYC Pride selected the Grand Marshals to recognize their resilience, activism, and diverse contributions to uplifting the queer community and advancing LGBTQIA+ progress in New York City and beyond.

"Our marshals this year remind us that we are stronger when we are united in our fight for equality and liberation," said NYC Pride Co-Chair Kazz Alexander. "They reflect the understanding that LGBTQIA+ rights are human rights."

"We're honored to put a spotlight on this incredible group of doers and change-makers as we come together in solidarity, celebration and protest," said Michele Irimia, NYC Pride Co-Chair. "Their participation is a powerful example of the enduring spirit of our community."

Karine Jean-Pierre blazed trails during the Biden-Harris administration as the nation's first Black and openly queer press secretary. Her rise in the political world is an inspiring example of the power of visibility and public service. "As a native New Yorker, this moment is deeply personal. It's more than an honor – it's a homecoming," Jean-Pierre shared. "New York is where I found my voice, where I stepped into the light, and where I first discovered the strength of community as an openly queer person. Now, at a time when unity is more vital than ever, we march – hand in hand, arm in arm – not just in resistance, but in remembrance, in celebration, and in unshakable pride. We are here. We rise. We endure."

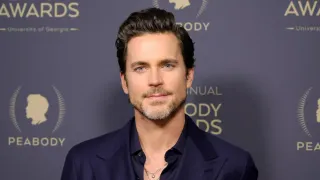

Marti Gould Cummings is also no stranger to making history. In 2021, Marti became the first non-binary candidate to run for public office in New York City. And as the first drag artist to moderate a panel at the United Nations, discussing ways to bolster LGBTQIA+ representation in global politics, Marti has fearlessly advocated for a society that embraces and celebrates diversity. "Pride is a protest, it began as a riot, and we must hold onto that. Trans people are being vilified and eradicated. As grand marshal I am honored and will use this platform in any way that I can to bring awareness to the grave issues impacting the most vulnerable within our community," Cummings said of their involvement.

Uplifting and protecting our LGBTQIA+ youth is central to NYC Pride's mission, which is why we're proud to honor Trans formative Schools. Its team of trans and queer teachers are building a new model for inclusive education with after-school programming that centers trans joy and social justice. Trans formative Schools' leadership team said: "In a time when trans kids are a target, from your local school board to the White House, Trans formative Schools is honored that our trans students and trans teachers can lead this protest as the Youth Activist Grand Marshals. However, we need cisgender people to know that trans visibility isn't enough – we need everyone to rise up and build a movement that uplifts and invests in trans lives, right now. Donate to trans led organizations – they know about ending transphobia because we live it every day."

Elisa Crespo broke barriers in 2020 as the first trans woman of color to run for public office in the Bronx. Through her advocacy work with the NEW Pride Agenda, she played a key role in establishing a state fund to support trans and non-binary wellness and equity, securing insurance coverage for PrEp, and passing the Safe Haven for Trans Youth and Families act. She remains a leading force for change, funding LGBTQIA+ causes across the country as Executive Director of the Stonewall Community Foundation. "I am thrilled to be selected as a Grand Marshall for NYC Pride - the city that raised me. My pride is rooted in resistance and love. In a world that tells us Queer people we don't belong, we must show up and demonstrate possibility models for the next generation," said Crespo.

Amid a wave of legislative attacks on the trans community, Lina Bradford - known professionally as DJ Lina - embodies advocacy for Black trans women. Getting her start as a member of the New York Club Kids scene, she has grown into the jewel of New York City's queer nightlife crown. Through her work with local groups like SAGE and GLAAD, she has expanded her influence beyond the nightclub. "To hear that I was thought of by my community for such a huge honor is something I would've never ever imagined growing up. I am humbled, honored, blessed and grateful for this opportunity to support and represent my community," said Bradford.

The NYC Pride March, among the largest and most significant LGBTQIA+ marches in the world, kicks off at 12:00pm ET on Sunday, June 29. Reflecting this year's theme, Rise Up: Pride in Protest, our Grand Marshals will be joined by millions of spectators, supporters, and allies as we reflect on the Pride movement's origins in protest and march in defiant celebration, advocacy, and solidarity.

Other NYC Pride programming in 2025 includes PrideFest, the largest LGBTQIA+ street festival in the United States, and Youth Pride, an inclusive celebration for the LGBTQIA+ community under 25. NYC Pride's full events calendar for 2025 will be announced soon.

NYC Pride is made possible through the support of community members and allies. To sustain our mission and continue advocating for LGBTQIA+ rights, we invite everyone to donate at nycpride.org/donate. For volunteer opportunities and other ways to get involved, visit nycpride.org/support-pride/ways-to-give.